Breathless costs counted

Breathlessness is costing the Australian economy at least $12 billion every year.

Breathlessness is costing the Australian economy at least $12 billion every year.

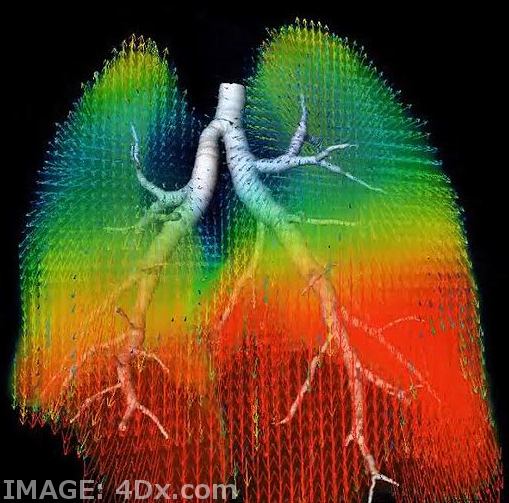

New research, conducted by The George Institute for Global Health, estimates both the direct healthcare and productivity losses due to breathlessness from various conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, heart disease, obesity, and anxiety.

According to the study, around 10 per cent of Australian adults experience clinically significant breathlessness.

These individuals are more likely to be unemployed and report lower quality of life than those without the condition.

The study is the first to quantify the social and economic impact of breathlessness, describing the condition as “an invisible disability”.

For those with severe breathlessness, the impact on their quality of life is comparable to that of lung cancer patients.

The research, based on a survey of more than 10,000 Australian adults, conservatively estimates the annual healthcare cost for breathlessness to be $11.1 billion, with an additional $1.1 billion in productivity losses.

The data also reveals that nearly three-quarters of adults experiencing breathlessness are under the age of 65, with a mean age of just 43.

Anxiety was found to be the most common comorbidity among this group.

But lead author Dr Anthony Sunjaya notes that the findings are likely underestimations, as the data predates the COVID-19 pandemic and excludes the growing respiratory health burden on children.

“The results are shocking enough, but they are conservative...we did not factor in children, who have increasing rates of asthma and obesity,” he said.

The study found a clear link between breathlessness and employment, with individuals experiencing severe breathlessness being 70 per cent more likely to be unemployed than those with mild symptoms.

It also highlighted a gender disparity in the impact of breathlessness, as women with two or more chronic conditions were more likely to experience reduced employment compared to men with the same severity of breathlessness.

Individuals with breathlessness are also more reliant on healthcare services, with double the likelihood of needing urgent GP visits and 2-3 times the likelihood of requiring frequent interactions with specialists.

Dr Sunjaya has called for stronger primary care systems to manage breathlessness.

“Most people with breathlessness receive care from GPs, so we clearly need to strengthen capacity in primary care to manage this debilitating symptom,” he said.

The prevalence of breathlessness is expected to rise as cardiopulmonary health worsens due to factors such as increasing obesity, air pollution, and climate-induced events like bushfires and dust storms.

These environmental factors further exacerbate conditions that lead to breathlessness.

Australia’s Lung Foundation has launched the Lung Learning Hub, aimed at educating healthcare professionals on diagnosing and managing breathlessness.

Print

Print